5.6 The Cultural Civil War

advertisement

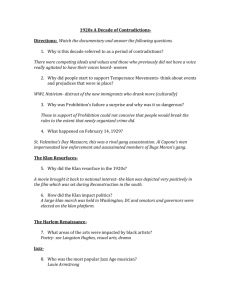

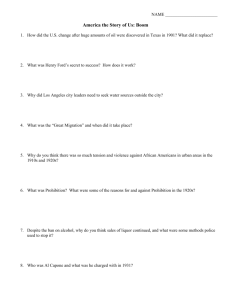

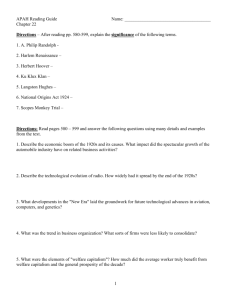

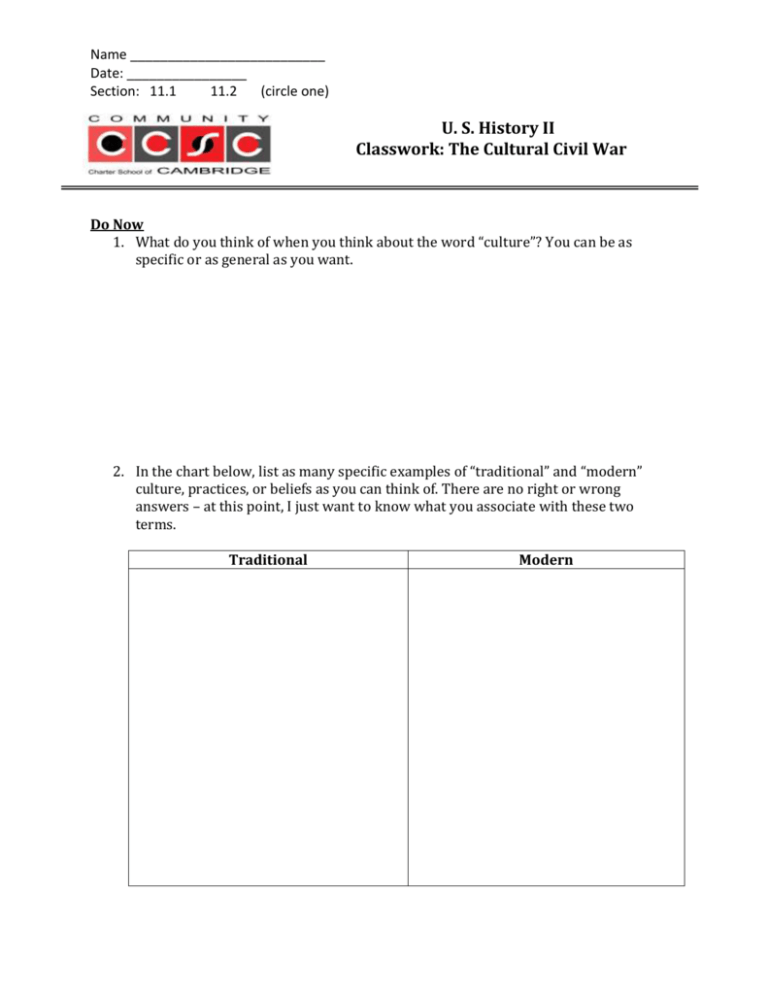

Name __________________________ Date: ________________ Section: 11.1 11.2 (circle one) U. S. History II Classwork: The Cultural Civil War Do Now 1. What do you think of when you think about the word “culture”? You can be as specific or as general as you want. 2. In the chart below, list as many specific examples of “traditional” and “modern” culture, practices, or beliefs as you can think of. There are no right or wrong answers – at this point, I just want to know what you associate with these two terms. Traditional Modern Exit Ticket In at least 5 complete sentences, explain: How did cultural change in the 1920s represent the conflict between traditional and modern values? Your answer should refer to specific aspects of American popular culture. Name __________________________ Date: ________________ Section: 11.1 11.2 (circle one) U. S. History II Classwork: The Cultural Civil War Instructions: Use your lecture notes, the attached reading, and other classwork from this unit to fill in the following chart. Bullet points are fine (see the first example) – but make sure you are capturing the disagreements between the traditional and modern sides of the “cultural civil war.” Urban vs. rural The Scopes Trial The economy Alcohol Music Women’s lives Fashion What’s traditional? Living in rural areas People lived and worked on farms What’s modern? Living in cities (urbanization) Often crowded, unsanitary Factory work Reading: The Cultural Civil War Note: This reading is adapted from a transcript of a video called “1920s: A Cultural Civil War,” narrated by Peter Filene. The video, the transcript, and related resources can all be found at http://www.dlt.ncssm.edu/lmtm/docs/culture.htm. Most people think history is about kings and presidents, wars and elections. But historians also study what ordinary people were doing and thinking in their everyday lives. This is what we call social and cultural history. Today I want to take you back to the 1920s and focus on some social and cultural developments: namely, sexuality, drinking, and religion. By the end I hope you’ll understand that Americans were engaged in a cultural civil war. They were fighting with words and laws, not guns—arguing about what kind of society America should be. On one side were those groups who wanted to loosen the rules of behavior and attitudes. On the other side were groups who defended traditional behavior and attitudes. The Rebels Let’s begin with a front-page story from the New York Times in February 1922. Several boys were having a problem dealing with girls. But it wasn’t the problem you may be imagining. The boys went to their mothers and said: “Mother, it is so hard for me to be decent and live up to the standards you have set me, and to always keep in mind the loveliness and purity of girls. How can I do it with this cheek dancing, and if I pull away they call me a prude. And when I take a girl home in the way that you have told me is the proper fashion she is not satisfied and thinks I am slow.” Girls like these were called “flappers.” They had bobbed hair and powdered noses. They wore fringed skirts just above the knees and stockings rolled below the knees. They held a cigarette in one hand and a man in the other. They checked their corsets in the coatroom before they danced to jazz. A revolution in morals was taking place… among certain Americans, at least: young, college-educated Americans who lived in large cities like New York and Chicago. The revolution had begun years earlier. Already in 1906 a journalist had proclaimed that “sex o’clock had struck.” But the new attitudes and behavior became more widespread and visible after the First World War. The Consumer Economy The consumer item that was most influential in fueling the revolution in morals was the automobile—especially the Model-T Ford. By the middle of the 1920s, a new Model T was rolling off Henry Ford’s assembly line every 10 seconds. And at $290 almost everybody could afford one. By the end of the decade there were 26 million Ford owners, one for every five Americans. But you may be wondering, how did these cars change morality? Well, picture a young couple on a Friday night in a small town. Instead of sitting on the front porch or strolling along Main Street, they could drive off in their Model-T. Away from scrutiny by parents and others, they could do whatever they wanted together. Dating was invented in the 1920s. Previously, young people had gone around in groups. But now they began to go out as couples. The average Ohio State coed [female college student] dated four nights a week. At Northwestern University, things got so out of hand that the women declared “dateless nights.” If the automobile permitted dating and petting, movies encouraged it. Movies were a big part of the consumer economy. They were America’s favorite form of entertainment. Middle-class people sat in overstuffed seats in lavish theaters—”movie palaces”—and listened to live music as they watched silent films. There was also a new meaning for “making love.” Before the 1920s, people said they made love when they flirted or wrote passionate words in letters to each other. Now they meant what we mean by that phrase: sexual intercourse. By the end of the 1920s, almost 2/3 of college women said they were willing to sleep with a man before marriage. And one fourth of them did. Among couples who were engaged to be married, the rate was even higher. The Traditionalists On the contrary, a large number of Americans did NOT think such girls could retain moral integrity. I want to turn our attention to these Americans—the ones on the traditionalist side of the cultural civil war. Who were the defenders of tradition against the new morality? The defenders of established values had antithetical [opposite] characteristics: The rebels were young. So their opponents were older. The rebels tended to be better-educated. So their opponents were less-educated. The rebels lived in cities, especially in the north and west. Traditionalists lived in small towns or rural areas, especially in the south. Older, less-educated, small-town or rural Americans wanted to preserve the kind of society they had grown up in. It was a society where women acted not like men, but acted “womanly,” where people enjoyed sex only after they married, where people didn’t think that happiness came from buying things, where people defined right and wrong according to the Bible. How did they defend these values against the new morality? They organized two social movements. Prohibition The first movement had already achieved its goal when the decade opened. Prohibition of liquor became nationwide law in 1920, once the 19th Amendment was ratified. The “drys” had won. Who were they? As you just learned, the supporters of Prohibition tended to be older Americans, living in the rural South and Midwest, and strongly Protestant. We know that Prohibition didn’t succeed. On the contrary, people began drinking illegally. And to supply illegal liquor, organized crime grew more powerful. So the traditionalists’ victory backfired. The New KKK The second movement was the Ku Klux Klan. Note: I’m talking about the second Klan. It was significantly different from the first Klan, which organized in the South to repress newly freed blacks. The second Klan existed primarily in the Midwest and Southwest, small towns and cities such as Cincinnati and Akron. Indiana was the heart of Klan country. At its height, one-third of all native-born white Protestant men of Indiana were dues-paying members of the Klan. The second Klan wasn’t Southern and it wasn’t concerned with defending white supremacy. Instead, the Klan members believed that modern America was becoming immoral: money-making, drinking, extra-marital sex. They blamed people not like themselves: namely, immigrants, Catholics, Jews, and young people, especially young women. By 1923, 3 to 4 million Americans were members of the Klan. That was 1 of 10 white, Protestant, native-born men. But like the Prohibitionists, the Klan was defeated in the cultural civil war. In 1925 corruption and scandals among leaders became public - Grand Dragon [KKK leader] David Stephenson allegedly kidnapped and raped a woman who later died, either from taking poison or from infections by bites on her body. Stephenson was convicted of 2nd-degree murder. Conclusion What lesson do I want you to draw? You’ll forget the details, but want you to take away a pattern of meaning. This story about the 1920s also holds true for eras before and since then. Innovation triggers resistance. Certain Americans—usually younger, better educated and urban Americans—calf for new ways of behaving and thinking. In response, other Americans—usually older, less educated, non-urban, Protestant— defend traditional values.